The Women’s Jail

When I healed from the trauma of the boat accident, my feelings about the boat accident changed forever. I felt different inside because the frozen traumatic energy was finally put to rest. I was no longer waking up in the middle of the night and calling myself a failure. It felt as if I regained some of my self-worth. Before I healed, the boat accident made something that happened forty-five years ago, feel like it happened yesterday. This unhealed trauma was always in the present when I thought about it. But after healing it, something had been restored, something had been put to rest. And now, it was finally in the past.

I was a prisoner of trauma and didn’t know I held the key.

I couldn’t believe how different I felt. Before, the feeling inside me was like my feet being pressed on the gas and the brakes at the same time. And now, it felt like I was in neutral. I didn’t understand why I felt so different, but I would in time. All I knew was I wanted to share my story. If I could change my negative feelings, maybe I could help someone change theirs.

I was telling everyone my story of how my feelings changed. Family, friends, even people I didn’t know. All my life I’d felt uncomfortable talking to people I didn’t know, and now I was talking to whoever would listen to me. Before I used art as a bridge to connect with people. Art was a safe medium between me and them. But now, I wanted to connect with people myself. I’d always had a real hunger to connect emotionally with others, and now I could do that, by sharing my story.

I was at my brother-in-law’s birthday party and met a woman, Kristin Saito. She was a director for Five Keys, the first charter school to teach in the Los Angeles jail system. I told her my story and she said I should create a workshop and teach it in the women’s jail. I’d never been to jail, but it sounded like a great idea to me. When I told my wife, she thought I was crazy. In the end, she supported me. It would be a big change in my life’s direction. But if healing allowed me to go from one moment feeling like a failure, to the next moment not, I had to follow the feeling.

Talking with Kristin about the workshop, we didn’t know what type of art form should be used to express the trauma. Should it be drawing? Painting? Sculpting? Kristin finally asked me, “How did you do it? How did you heal your trauma?” Well… I did it through screenwriting. Being able to see myself as a character in a movie brought perspective, understanding, and finally forgiveness to myself, for a moment that always consumed and overwhelmed me. I then sent her a copy of the boat accident I had written. The power of the traumatic moment was written on the pages. She was blown away by it. It was clear that screenwriting would be the platform for the trauma. From the beginning, the development of this trauma screenwriting workshop wasn’t a straight line. It’s been a constant learning and growing process for me.

The first day I arrived at the women’s jail in Lynwood, California, I was excited and hopeful. I stared at this big white concrete structure. It looked like any other nondescript industrial complex you would drive by without noticing. I was to meet a woman who taught classes in jail. She gave me a couple of hours of her class time each day to teach my workshop.

As soon as I entered the jail, the energy got very real. It’s a different world in there. The lines of power were clearly drawn. To get into the main part of the jail, you put personal items, and cell phones in a small locker. You then waited for this huge sliding door to open. It was about a foot thick and automatically slid open like a freight elevator. You walked into a very small transitional room. It was here you gave them your Driver’s License. The deputies working on the other side of the glass checked if you were on the list. They stood among a wall of monitors that surveyed different areas of the jail. Riot guns, vests, and helmets lined the wall. Once you were cleared another big foot-thick door on the other side opened and you entered the jail. The system inside was locked doors with guards at different stations, pressing buttons and allowing you passage.

Heading down the hallway, I saw a group of incarcerated women walking towards me. They were all wearing yellow jumpsuits. When They got closer the guards escorting them made them face the wall as I passed. It was an uncomfortable feeling of power, I was in a different world.

After walking deep into the bowels of this concrete labyrinth, I finally reached my destination. About thirty women aged 20 - 60 filled the classroom. They all stared at me like who is this guy? What’s he trying to sell? They’d heard it all and seen it all and had reason not to trust anyone. There was every race in that room. Many looked like they were from gangs. I sat there thinking “What am I going to tell these women that they’ll listen to? How do I make what worked for me, work for them?”

The teacher was Aileen Hongo, a tiny Japanese woman teaching a life skills class. She was small but had strength. She spoke with confidence and openness to the women. They trusted her. When it was my turn to speak, I just started telling my story. I told them about the boat accident and how it left me with feelings of disconnection and low self-worth. I could see in their eyes that they understood how that felt. I told them how I healed and changed those feelings by writing about the boat accident like a screenplay for a movie. I asked the group if anyone had something they wanted to write about. Immediately a woman raised her hand. She started crying and talking about her young son. He would visit her with his grandma and stare at her through the glass in the meeting room. She wanted to hug him and tell him how much she loved him. But she knew she wouldn’t be able to because she was in for three life sentences.

The class went on a short break and left the room. I started thinking, how am I going to help this woman? What kind of moment in a screenplay could she write? As the class came back I had an idea. I asked the woman, what if you wrote a scene about your son coming to see you in jail? You see him getting ready at home with grandma and he’s scared because he doesn’t like the jail. He arrives with his grandma to visit, and you both see each other in the meeting room divided by glass. You tell him how much you love him, how much you miss him, and wish you could hug him. As he leaves you tell him, “The next time you feel the wind blow, that’s me giving you a hug.” Your son nods his head and they leave. The boy sits in the backseat driving home with his grandma. As a warm wind gently blows in through the window and wraps around him, he smiles. When I said this the women smiled and said “Aaahhhhh.” It was then I knew I was onto something.

The screenplay allows you to see your world.

I began to talk to the women individually, seeing what moment they might want to write about. Not everyone was open to the process. One woman said, “Why would I want to open up that can of worms?” True enough.

I spoke with a heavy-set Mexican woman in her twenties with frizzy hair and a big smile. She wanted to write about the time she broke her neck in a car crash. She was at a friend’s house partying, and another friend said “Let’s go for a ride.” They jumped in his car and continued partying, smoking, and drinking. He started getting paranoid as he drove, quickly exiting the freeway, driving fast he lost control and hit a tree. She was sitting in the backseat and slammed her head into the dashboard. She woke up in the hospital with a halo and screws bolted into her head. As she’s telling me the story, she has a big smile on her face the whole time. In the hospital, her sister says the guy who was driving the car wants to come and see her. She’s angry with him and says no. A few weeks later she finds out that he was killed in a gang fight. She goes quiet but is still smiling. I tell her to start writing that.

I talk to the woman next to her. She wants to write about the time her boyfriend tried to kill her. She was at his place and they were both high on methamphetamines. Her father had just gotten out of prison. He called her and said he was coming over to kill her boyfriend because he was from a rival gang. She and her boyfriend jumped in his car and took off. They were flipping out high on drugs, he pulled the car over by the train tracks. He dragged her out of the car and started stabbing her with an ice pick. She screamed, “I’m pregnant!” She wasn’t, but it got him to stop and drive away. I said ok start writing that story. I was talking to the next woman when suddenly I heard someone start to cry. I looked over and saw it was the woman who got stabbed with the ice pick. She was helping the woman with the big smile on her face and said, “I’m crying for her because she can’t cry.”

Some of these women had been through so much in their lives and had so much strength and empathy.

Another woman was sitting in the middle of the room, she was the class clown. I asked her what moment she wanted to write about. She said the time she was hit by a cement truck, right before she came to jail. Everyone in the class laughed, and she loved it. I sat down with her and asked if anything happened before that, and how was her childhood. She was very animated and said she had a great childhood. She grew up back east in the forest. Her parents ran illegal gambling houses and were always “cooking the books”. I asked if anything happened to her when she lived there. She thought for a moment, then said when she was eleven she was walking in the woods, touched a plant, and got paralyzed. She lay in the forest unable to move. No one came looking for her. After two days she could slowly move again and crawled back home. I asked her if anything happened before that. Her manic energy suddenly shifted and she got very quiet. She said when she was two years old, her parents would take her to the basement. Down there against the wall were cages full of rats. When her parents didn’t have time for her, they left her with the rats. Like most of these women, she grew up very neglected. She learned early on that she wasn’t worth her parent’s time. Carrying low self-worth and no support system, she went from trauma to trauma, until she was hit by a cement truck and stumbled into jail.

As my time went on in the jail I began to get a handle on my workshop. Talking to the women, encouraging them to find the earliest trauma they could remember. By getting to the earliest trauma, you get closer to where the first disconnection happened, where part of themselves got left behind. People can have many traumas, the earliest is where the first pain got stuck. Once we find the specific moment, I have them write their Raw Material. The raw material is what I call free-flow writing, writing about everything they remember from the traumatic moment. How old they were. Who was there? Where did it happen? In the kitchen? What did the kitchen look like? Flushing out all the details they can remember. This can be a very emotional process, tapping into feelings that you disconnected from and locked away to survive the moment. Being vulnerable, being seen, sharing your truth, often for the first time. We then use this raw material to write the screenplay version of their story. When structuring their screenplay I ask them to think about three specific feelings regarding their moment. How did you feel before the moment? How did you feel when the moment happened? How did you feel after the moment? What life looked like moving forward. This last part is often a very lonely feeling. I then take their raw material and begin to write their First Draft of their moment. I help them start their story in screenplay format. It’s a different way to write. When you read it, you see yourself as a character in a movie.

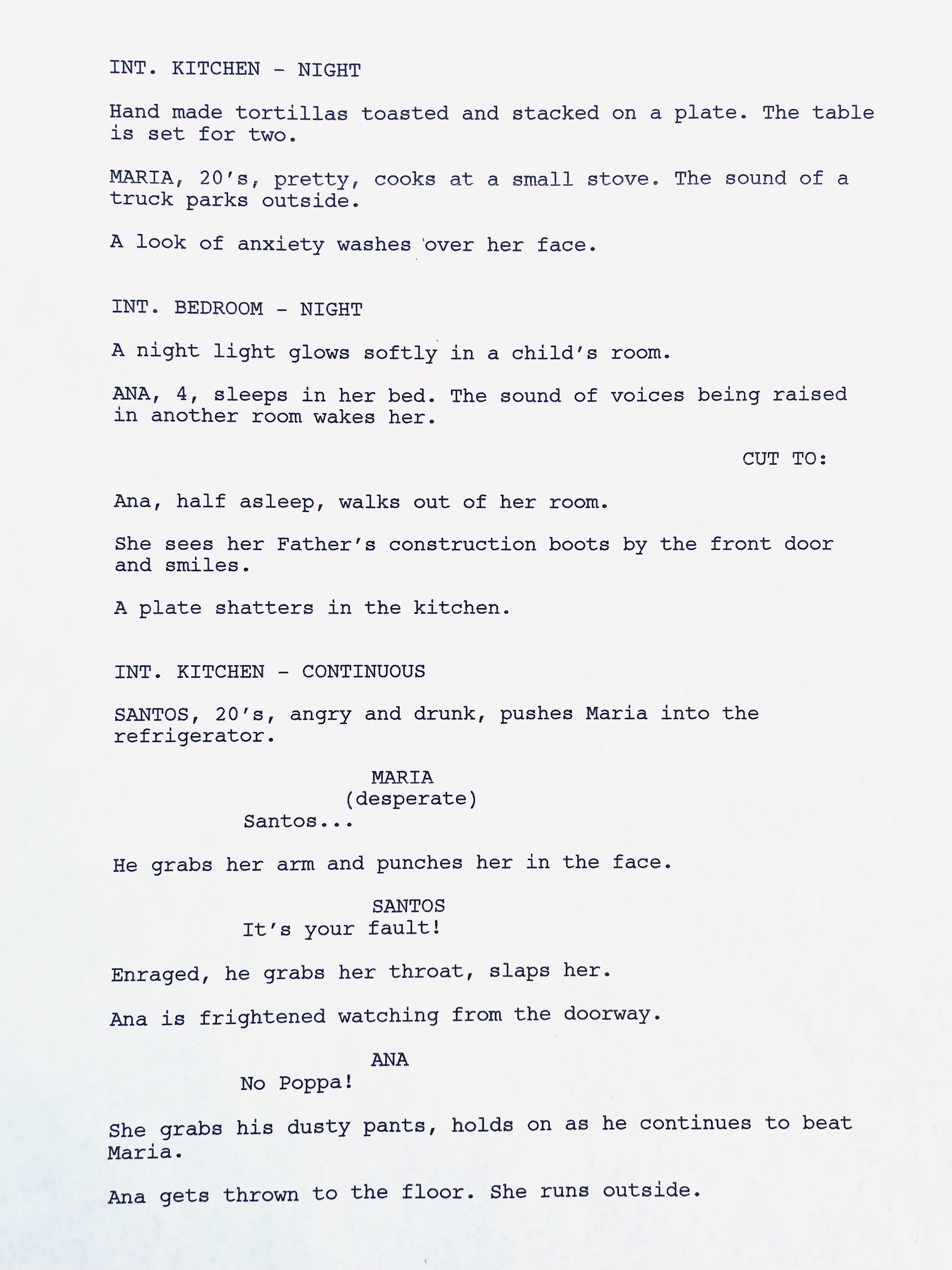

One of the inmates was a woman who I’ll call Ana. She was Hispanic, in her twenties. She started crying, telling me she wanted to write about the moment when she was four years old and saw her father beat up her mother. The workshop process goes like this, talking about it, writing the raw material for it, writing the first draft in screenplay format, rewriting the second draft, fine-tuning, and writing the final draft. Here’s Ana’s Final Draft.

Ana ran outside and hid in the back of her father’s truck. When her mother ran out bloodied and broken she tried to get Ana to leave with her. But Ana refused, she blamed her mother for what happened, and she blamed her for many years. But now it had been twenty years since that moment happened. Ana was in jail now, and her mother was taking care of her young son. She never understood why she blamed her mother for the time her father beat her up. But she was older now and started to get a clearer perspective of what happened by writing about it. She was sorry she blamed her mother. We came up with an idea of how to end her story from inside the jail where she was today.

Writing about this moment began a healing journey for something Ana had carried for so long. She couldn't wait to share her screenplay with her mother.

I heard many stories, unbelievable stories. Every two months was a new semester and a new classroom of incarcerated women. Me and Aileen started going to classrooms in higher security areas of the jail, modules that had only 10 inmates. They would come out of their cell and be handcuffed by guards to a steel table where we would do class. Sometimes I would pull a chair up to their cell door and talk to them through the opening where they passed the food. Most of these women looked like any other woman you might see in a supermarket or on the street. One woman couldn’t walk, she got around in a wheelchair. Out of her cell, the guards handcuffed her to the steel table bolted to the floor along with her wheelchair. She didn’t look like a killer, she looked more like my friend’s mom, a little overweight, confident, with a whip-smart mouth. She was accused of doing something really bad to her sister, but she said she was innocent. She told me she had done therapy and addressed her traumas already and didn’t want to do the workshop. I didn’t argue with her.

I wasn’t concerned with what they did to get in jail. Was it an accident? Maybe. But I don’t think there are many accidents when it comes to how we feel emotionally. And our feelings are at the root of our actions. There is a cause for how we feel emotionally, and many times that cause happened a long long time ago. That’s what my workshop is all about, getting back to the root cause that is buried beneath it all. This is how we survive overwhelming moments. We disconnect, and the pain gets buried to the point that it’s almost forgotten because we’ve hidden it and denied it for so long. But it’s alive. Those hurt, painful, shameful feelings are alive unconsciously guiding us. That child who was left behind is waiting for someone to finally see them.

I was in the process of starting to work with the men at The Los Angeles County Jail. But my plans got derailed when a new Sheriff came into town. He cut the Five Keys program whose umbrella I was working under. After volunteering for a year and working with these women, my time was over. The experience was transformative, and set a path for teaching my workshop on the outside.

I heard you need two things to heal trauma. First, you need a safe space, that’s the workshop. A place where you can feel safe and let your armor down, the same armor that is protecting you from feeling the buried pain. Once the armor is down, the pain can come up. And then you need the second thing, a place to put the pain. And that is the screenplay.

To shield our pain, sometimes we become a prisoner within our own armor.

Look deeper.

Emotional pain boils down to a feeling, and that feeling is from something that happened. Maybe that something was neglect or criticism from a parent when you needed connection. Or maybe that something was an act of violence towards you. It can be challenging to address these moments. When you think about an unhealed traumatic moment, it feels the same as it did when it happened. You were a child and disconnected from the moment because it was overwhelming. Now you’re an adult, but you feel the same feeling and energy that got stuck and never processed. It’s alive and waiting there. To use a metaphor, it’s your inner child waiting for you, waiting for the adult to come and save them because no adult was there to help them when it happened. When that moment got stuck, we started building our armor, our survival system around it, so as not to touch the pain.

It’s what Dara Marks, the screenwriting guru, calls The Fatal Flaw. She says, “As essential as change is to renew life, most of us resist it and cling rigidly to old survival systems because they are familiar and “seem” safer. In reality, even if an old, obsolete survival system makes us feel alone, isolated, fearful, uninspired, unappreciated, and unloved, we will reason that it’s easier to cope with what we know than with what we haven’t yet experienced. As a result, most of us will fight to sustain destructive relationships, unchallenging jobs, unproductive work, harmful addictions, unhealthy environments, and immature behavior long after there is any sign of life or value in them. This unyielding commitment to old, exhausted survival systems that have outlived their usefulness, and resistance to the rejuvenating energy of new, evolving levels of existence and consciousness is what I refer to as the fatal flaw of character.”

“The Fatal Flaw is a struggle within a character to maintain a survival system long after it has outlived its usefulness.”

I believe with support, encouragement, and guidance, you can face the cause that continues to generate those old fearful feelings. You can finally complete the survival response that got stuck. Put those feelings that have been held over your head since you were a child finally to rest.

When I was writing the screenplay of the boat accident, I asked my dad about it. I wanted to know how the experience was for him. He was the one driving the boat. It was his best friend, who I called my uncle, who had drowned. He thought for a moment, then said “I don’t like to think about it.” I said ok and dropped the subject. This is how he lived with the many traumas he had endured throughout his life. About a year later I was teaching my workshop in the women’s jail, I told my dad about it. He thought it sounded really interesting. A few months later he asked me if I was still going to the women’s jail. I told him I was, that it was helping the women address their traumas and begin the journey of healing. He was happy to hear that and thought it was great. Then I told him “And you know what? I wouldn’t be able to do this work if it wasn’t for the boat accident.” He looked at me and understood. Then I said, “See Dad, something good came out of it.” He nodded his head and gently smiled.

There are many ways to address trauma, my workshop is just one of them. If you’re curious or know someone who may be curious, please share my work with them, email me from my website, and we’ll find time to talk. I’ll share with you stories from the workshop, about how healing, creative, and empowering it can be. There are many ways to address and begin to heal trauma, I encourage you to find one.

So if you keep finding yourself feeling like you’re not good enough, feeling like you’re running from something, feeling like you’re looking for approval… then look a little deeper. I encourage you to get curious about that uncomfortable feeling. If you don’t look away, if you stay with the feeling, you might find it goes back to childhood, back to a specific moment, or several moments. Then notice how these moments still feel like they happened yesterday. That’s because they’re still alive. Now dare to not bury this uncomfortable feeling. Have the courage to look at what really happened. Dare to speak your truth. Dare to be vulnerable, because that’s where the healing begins. It’s not your fault. And you’re the only one who can change this feeling inside you.